Gimmick Infringement Volume 2: Make the Gimmick Infringement Your Own Edition

Greetings, and welcome to another edition of Gimmick Infringement, a feature wherein we take a look at one iteration of a gimmick match available on the WWE Network (sorry, this author knows it’s a weird time to be giving Vince money, but that back catalog has been on non-stop while I teach from home). Some are iconic for their success, others for the extent to which they flopped, and some just...happened.

We defined a "gimmick match" as, in any way, adding a rule/stipulation to or removing a rule from a match, changing the physical environment of a match, changing the conditions which define a "win", or in any way moving past the simple requirement of two men/women/teams whose contest must end via a single pinfall, submission, count out, or disqualification.

This month, yours truly had a grand plan for a focus on the Triple H versus Cactus Jack Hell in a Cell match from No Way Out 2000, but then the WWE Network had to go and do an Untold feature on it and its Royal Rumble predecessor. It’s a fantastic feature and really gives some great insight into one of the less lauded, but still vitally important, feuds of the Attitude Era, but it also completely killed any original thought I might give to Mick Foley’s true greatest Hell in a Cell match.

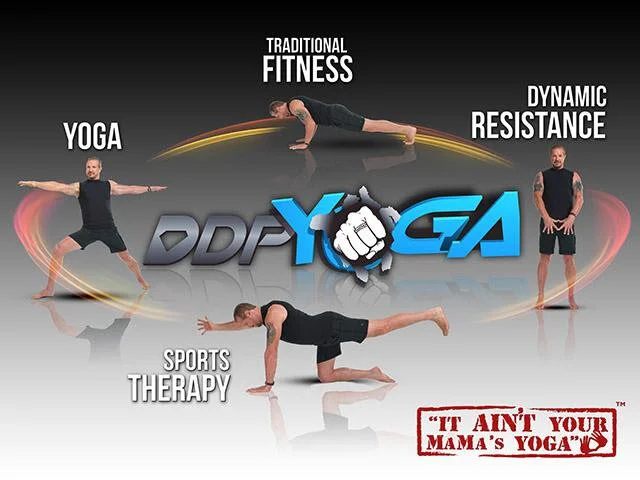

Taking a different approach, I decided to lean into something I’ve used to fill a lot of my quarantine time when I’m not teaching and directly parenting: DDP Yoga, which I started in early April and which has been a great help in keeping my legs fresh for running (which weightlifting used to do, but the building where all the weights and treadmills are kept is closed). Like we used to do in the 90s when WWF wasn’t available, let’s change the channel to WCW, flex the quads, flex the glutes, reach out, grab the ball, and settle in to chat about Diamond Dallas Page’s string of hardcore brawls with Raven in the spring of 1998.

1998 and the Power of Positivity

As I mentioned in my piece about Shawn Michaels, my early wrestling fandom intersected with some difficult parts of my childhood and often served as an escape from those difficulties. My WWF hero was always The Heartbreak Kid but, as the summer of 1997 began, life took a turn and my hero was absent for two reasons.

One was HBK’s own smile-losing backstage issues, which we’ve detailed before, and the other was a change in my living situation: I was placed in a foster home at the end of my sixth-grade year which, luckily, was a family of wrestling fans but, unluckily for the directions WWF product was taking at the time, had very conservative religious views that led them to shy away from Vince McMahon’s content, which only grew edgier as 1997 wore on. More often than not, Nitro was on the family’s television on Monday nights, especially if Sable, Goldust, D-Generation X, or Stone Cold Steve Austin were onscreen on USA Network.

My wrestling balance now favouring World Championship Wrestling by a nearly 3:1 ratio, I saw the rise of another hero whose gutsy battles with the New World Order echoed a lot of Michaels’ babyface runs: the charismatic Diamond Dallas Page. Page’s constantly taped ribs made him a vulnerable everyman in the same way that Mr. WrestleMania’s constant threat of concussion (and perpetual size mismatches) always had, and his creative means of attacking the black and white baddies like disguising himself as a luchador or feigning a heel turn were bright spots in a WCW product that always ended with Hogan, et al, standing tall.

With this family having the means to buy pay-per-views (which I did not have at my normal home), for the first time in my life I got to see live, long-form wrestling as it happened, and the WCW undercards of 1997 and 1998 tended to be, in my memory, works of art ruined only by the start of a Hollywood Hogan and/or Kevin Nash contest in the main event. Alongside the cruiserweight division consisting of men half his age but with the same amount of time spent in the squared circle, Page quickly grew into a highlight of these WCW PPV specials, and always crossed the curtain with every intention to steal the show.

While Page fought the good fight on behalf of the WCW loyalists and garnered fans’ attention for the “regular guys” who refused to cede their 18’ x 18’ ring to invaders, a recent signing from the world of hardcore wrestling took a different approach and demanded attention by asking, “What about me? What about Raven?” Carrying over his narcissistic, grunge-inspired cult leader persona from ECW, Raven acted onscreen a bit like Hogan acted backstage: he dictated when, where, and whom he would fight, and would demand the match be held under his personalised “Raven’s Rules” (essentially no holds barred, but expect weapons). Often, if he did not feel like competing in a particular match, he would send one of his Flock (like Billy Kidman, Perry Saturn, former American Male Scotty Riggs, or “Sick Boy”) to take a pin for him.

Raven wore the shirts of all the bands whose tapes I snuck back into the foster home after weekends out on visits to my regular home, and possessed a kind of “cool” that made it seem like dirty and outcast might turn out to be fashionable (which he squandered by treating everyone around him exactly like the “in crowd” would treat someone dressed like him at any middle school in the 90s).

His feud with Diamond Dallas Page grew out of an existing feud between Page and Chris Benoit, and ignited an excellent Falls Count Anywhere Triple Threat Match at Uncensored (that fits the bill for this column, but I’m too emotionally exhausted by 2020 to write anything more than a passing mention of Chris Benoit). Speaking of excellent undercards with atrocious upper cards, this Uncensored PPV featured a Bret Hart vs. Curt Hennig match (where all of the backstory was just their WWF history), and a Hulk Hogan vs. Randy Savage cage match in the main event that had zero finish whatsoever (literally, the NWO interferes, Sting rappels down from the ceiling, Savage decks Sting and then leaves as Hogan yells at him from inside the cage).

Benoit split off into his own feud with Booker T over the Television Title, as Raven and DDP continued to battle first over Page’s United States Championship. In a “yes, this really happened” moment, Diamond Dallas Page was appearing on MTV alongside The Foo Fighters and Carson Daly, when Raven attacked him and stole the United States Championship Belt, declaring himself the new champion.

Page, a longtime ally of Raven’s from his Scotty Flamingo days, cost Raven a match against Buff Bagwell on the following Monday Nitro and exposed the grungy outcast as a spoiled rich kid slumming it and playing dress-up on national television. Playing on their shared history being trained by Jake “The Snake” Roberts, Page emphasised how he, with his hard upbringing and absentee father, had it way harder than Raven; but tried to make his life, and the lives of others, better, while Raven continued to be a rich and bitter bully.

Page and Raven would battle over the stolen championship at Spring Stampede which, spoiler alert for one of our two matches, resulted the very next night in Goldberg winning his first wrestling title on Nitro; now about blood rather than gold, Page and Raven continued their battle well into May for the second of our two contests.

The Rules

The first of our two matches is from Spring Stampede 1998, and is contested under Raven’s Rules, functionally the same as a WWF Hardcore Match or any ECW main event. There are no disqualifications, no count-outs, and pinfalls or submissions must occur in the ring.

The Bowery Death Match from Slamboree 1998, meanwhile, is a match occurring inside of a roofed steel cage containing two trash cans filled with various weapons. A win occurs under Last Man Standing rules, meaning that a wrestler must get to his feet before a count of ten or lose the match.

The Match(es)

For the very first time, we’ve got TWO matches to talk about in this section! It’s the greatest innovation in the history of our sport!

Raven’s Rules

To start off, let’s give a little bit of love for one of the best things about 1998 WCW: DDP’s old “Smells Like Teen Spirit”-aping WCW entrance music, which starts off our first contest. WCW was sorely lacking in the “video packages to explain each match” department, where WWF/E has always excelled, so we’re left with Schiavone and company breathlessly detailing the pair’s history as they enter the arena (while alluding constantly to more important goings-on in the show’s main event). Raven, meanwhile, enters to silence, his own “Come As You Are” take-off still being a few weeks away.

Before the match can even begin, Sick Boy (a member of Raven’s Flock) holds back Page for a belt shot from Raven, but DDP goes into Bent-Legged Bar Back and Raven hits his own lackey instead. As Raven recovers at ringside, Page hits a plancha to the floor, but gets distracted fighting off the Flock in order for Raven to throw a knee into DDP’s perennially injured ribs to take control.

The pair battle up the Bonanza-themed entryway to an old stagecoach, where Page first throws Raven off the wagon into a set of hay bales, then follows up with an elbow off its roof. Page whips Raven first through one set of decorative fences, then another, clattering his opponent with a trash can and its lid.

The pair destroy the WCWWrestling.com live broadcast set, a cake pan, and WCW’s VIP seating booths, before Raven attempts to put Page through a VIP-area table (but we’re not at 7:00 to go in Fat Burner 2.0, so there’s no Broken Table to be had here).

A bull rope (with cowbell) and another trashcan find themselves warped over Page’s back before Raven drags him back to the squared circle; there, a WCW-favorite weapon The Kitchen Sink is introduced to the exact same sarcastic dismay Bobby Heenan displayed when it was used in the previous month’s US Title Match. Tony Schiavone takes the opportunity to grab the lowest hanging fruit by noting, “So much for saying this match has everything but the kitchen sink!”

Page fights out of being choked with the bullrope to drop-toehold Raven into the aforementioned sink (“The ol’ Drano maneuver!” Schiavone intones) until Van Hammer, another Flock member, attempts to help Raven but also gets duped into hurting his leader (and takes a sink to the back for his efforts). Reese (Jo’s favorite Yetay) enters the ring to double-armed chokeslam our yoga teacher, but Page kicks out of the pin to take out each member of The Flock with a stop sign frenzy (dibs on that as a band name). When Billy Kidman attempts to choke Page from behind, DDP lifts him first into a piggy-back ride, then into an incredible Diamond Cutter that absolutely takes this match to the next level (no hulking it up or atten-tion afterward, though).

In a super-anticlimactic moment, though, immediately after the blueprint for RKO-outta-nowhere, Horace Hogan sneaks in to hit Page from behind with the stop sign, leading to a Raven DDT and a three-count (as well as an extremely accurate Bobby Heenan prediction for the shortest title reign in history). For a show whose poster featured a “clever” graphic indicating there would be “no bull”, this was an awful end to a great brawl.

The Bowery Death Match

I’ll give another point to WWF/E here: WCW never seemed to figure out how to best present cage matches on television. Both here and in the aforementioned abysmal Hogan-Savage main event from Uncensored, it’s extremely difficult to see what’s happening through the chain link in wider angle shots. Think ‘red Hell in a Cell’ difficult.

Anyhow, Raven comes to the ring with four guards in riot squad gear, which is neither a Chekhov’s gun nor a direct ripoff of when ECW debuted Rick Rude by having him come to the ring for weeks wearing a motorcycle helmet.

We start off counting it down with ten shots to the turnbuckle using Raven’s head, before DDP is driven headfirst into one of the still-filled trash cans. Of note: nearly every time the commentators mention the title of the match, the order of the words “Bowery”, “Cage”, and “Death” changes. Sometimes, according to the commentators, this is the Bowery Death Cage Match, other times this is the Bowery Cage Death Match, and a lot of the time the NWO has a match later tonight.

Raven upends one trash can to reveal fire extinguishers, a chair, and a shovel (things one would find in a bowery, Mike Tenay supposes), while the other contains last month’s bull-rope, a bunch of junk mail, a cookie sheet, and a VCR, for some reason. Page uses the bull-rope to vigorously adjust Raven’s neck and extend his spine into the walls of the cage numerous times, before going into touchdown to attempt to hang Raven from the structure’s ceiling.

Raven beats the ten count just to meet a VCR to the head, while the crowd chants either “E-C-W” or “V-C-R”. Raven shoves Page into one trash can, then batters him repeatedly with the other, before grabbing a cookie sheet (Schiavone reveals his utter lack of science knowledge by pontificating on the number of “RPMs” one could get behind a cookie sheet) and warping it over Page’s head. Somehow, despite the established 10-count for a win, the referee does the “three armlifts” thing as Raven has DDP in a sleeper hold, but Page explodes out in a way that rightfully punishes said referee with a bump into a trash can.

Somehow, in a match with “no rules,” the ref bump allows a series of interferences where The Flock fights past the riot police, only to be attacked by Van Hammer, who obliterates everyone with the stop sign and handcuffs Reese to the guardrail. Two riot police turn out to be Billy Kidman and Horace Hogan; the latter eats a lackluster Diamond Cutter before Kidman, hanging monkey-bars-style from the ceiling, gets pulled down into another spectacular Diamond Cutter outta nowhere. That’s two months in a row where the best spot in a DDP-Raven match is DDP hitting his finisher on Kidman. Raven nails Page below the belt to set up his own Diamond Cutter (and he does appropriately “hulk up” after), but Page gets to his feet and pulls Raven into yet another Diamond Cutter (are we seriously still in Ignition here?); Page just barely makes it back to his feet before ten as Raven stays down to give DDP the win.

One Riot Squad member stays back to handcuff the entire Flock to the sides of the cage in order to attack Raven, all while the commentators distractingly speculate about who the riot squad member might be (such helpful details as “it’s someone with long hair” and “maybe Raven owes him money” are on offer here). The man unmasks, revealing himself first to be Mortal Kombat ripoff Mortis, then to be Kanyon, who apparently is upset over being DDT’ed when he attempted to join The Flock weeks earlier, but nobody in the building (neither the performers, the crowd, nor the commentators) really seems to care.

My Ratings

Man, if these two matches aren’t WCW’s decline in a nutshell.

Chris Jericho detailed in his first memoir, A Lion’s Tale, how the WCW undercard flourished largely because the front office could not be bothered to take a direct role in managing it. By his description, much of their segments were (at best) lightly outlined by an Eric Bischoff determined to focus only on his own NWO-centric storylines; these segments tended to fall apart, though, when the office took notice and needed to inject their creative direction into the stories.

When these two matches are about the bell-to-bell story, and Raven and DDP are free to get creative with the ways they hit, slam, and generally punish each other, they’re a masterpiece. There are so many fun spots, from the business with the stagecoach at Spring Stampede to the wild and inventive (for WCW, at least) weapons at Slamboree. Left to their own devices (figuratively and literally), Raven and Page put on one hell of a show. The crowd is SUPER into everything Page does, and the Diamond Cutters (especially the ones Page does on Kidman) blow the roof off the building.

The fun breaks down as WCW’s broader storytelling and corporate policies inject themselves into the matches.

First of all, that both of these matches are a bloodless affair absolutely cheapens what happens from bell to bell. Blood wasn’t anathema to WCW at the time (both Hogan and Savage bled in a far less physical encounter than Page, Benoit, and Raven put on at Uncensored), and as WCW leadership declared that they were the more mature, more realistic product, the fact that smashing someone over the head with a VCR produces no visible wounds makes this more akin to Wile E. Coyote vs. Roadrunner than a realistic product.

Further, these matches lose their uniqueness with their placement on crowded and overly gimmicked cards; at Spring Stampede, the Raven’s Rules Match is sandwiched between a Baseball Bat on a Pole Match and another arena-spanning No Disqualification Match for the WCW World Heavyweight Championship (whose results were also negated 24 hours later). At Slamboree, any impact of the reveal-and-turn after the match is ruined by the fact that a far better masked reveal happens with the Cruiserweight Battle Royal earlier in the night (I’ll keep that under wraps because I don’t want to spoil anything for Jo, but it’s my absolute favourite moment in WCW history) and a far higher-profile betrayal happens in the main event featuring an intra-NWO battle for the tag team titles.

WCW shoots their own storytelling in the foot constantly with these matches; the portions where the established Flock members interfere are fine, if not excellent. They reinforce Page as the everyman People’s Champion and underline Raven as the spoiled rich kid taking shortcuts at every turn. Watching Page evade and fight off so many larger and grungier men (and give Billy Kidman the Diamond Cutter as acrobatically as possible) stirs the crowd into a frenzy, but when longer-term “storytelling” gets injected, the crowd (and the matches) die.

Horace is a charisma vacuum and, like many in WCW at the time, gets his push only because of his real-life connection to Hulk Hogan (in this case, Horace is Hulk’s real-life nephew, and this becomes kayfabe canon later in the fall). His reveal at Spring Stampede is confusing at best, and gets no reaction in the building because it just looks like a crew member is getting involved (fans watching the broadcast have Tony Schiavone broadly spelling out what happened, at least, but even that kills any pro wrestling mystique the moment may have had).

At Slamboree, Diamond Dallas Page overcomes months of torment (which, in storyline, stemmed from years of frustration dating back to his mutual training with Scott Levy, who would go on to be Raven) and is immediately forgotten the moment he celebrates his way back up the ramp. The story shifts completely to Kanyon’s reveal and revenge on Raven, and nobody cares. The Flock is not the reason why this story had an impact: Page was, and in his absence, the crowd does not care one bit (it could also be that, as we mentioned, outside of a tight closeup it’s impossible to see through the chain link of that cage).

That’s not to say these matches are bad; even 22 years after they were fresh, there were moments (the elbow off the stagecoach, the VCR shot, Reese choke slamming Page, everything involving Kidman) that made even jaded, almost-35-year-old me bounce on the couch like my six year-old when he plays Spider-Man. Whether due to WCW production value, Page’s meticulous planning, or both, they’re a much more polished and enjoyable version of ECW’s garbage brawls, at least until the finish.

The storytelling in those finishes exposes the biggest flaw in WCW at the time: Nitro ratings were the be-all, end-all metric of their corporate success. These ratings were more important than ticket sales (as evidenced by their tendency to hold both television and pay-per-views in locations where admission was free), more important than merchandising (very few wrestlers had decent, purchasable shirts, and WCW’s toy market would have had to improve a ton to be considered crappy), and more important than pay-per-view (which, in an inversion of the traditional formula, turned out to be a commercial for Nitro that audiences paid to watch, rather than Nitro being a commercial for the high-ticket product).

Spring Stampede’s finish was a commercial for Raven’s first (and only) defence against the surging Goldberg the following night, as well as the reveal of Raven’s mystery helper. Slamboree capped the feud by telling you to tune in tomorrow for Raven’s new story of betrayal, jealousy, and privilege, albeit with a character in whom audiences had invested far less than they had with Page. This was not inherently a WCW problem at the time (McMahon and company filled their 1998 premium shows with several RAW teases of their own, especially with the ongoing Austin-versus-everyone storyline), but with a few exceptions the WWF seemed a lot more capable of allowing their PPV moments to breathe for the live crowds and the fans paying upwards of $30 to watch at home.

Unfortunately, of the three hardcore pay-per-view brawls between Raven and Page in the first half of 1998, the best of the bunch is the triple threat from Uncensored which, though it’s the least plagued by WCW politics at the time, is tainted by one’s personal feelings about Chris Benoit in the present day (at least, it is for this writer).

Spring Stampede is, overall, the better product of the two we’ve covered in-depth here, and suffers the least from its dead ending (it needs to be said that the Kanyon turn-and-reveal feels like it goes on forever). For the Raven’s Rules match there, I’ll go 7/10, and the visual issues (and overly-long addendum) with the Bowery Cage Death Match (or is it Bowery Death Cage Match?) drop it to 6/10 for me.

Both of the Diamond Cutters Page delivers to Billy Kidman, though, get a solid 11/10.

Meltzer Says:

Big Dave goes **** for the Spring Stampede contest, and drops Slamboree down to **½.