That God Heat: The Weird History of Pro Wrestling and Religion

At some point in the early ‘90s, I sat in a ridiculously hot church in Fitzgerald, Georgia (a microcosm of possibly every Small Town, USA stereotype you can think of) for about three hours listening to one of my all-time favourite wrestlers, Jake “The Snake” Roberts, preach to an absolutely packed house. Now, I know “at some point in the early ‘90s” is super vague, but—and believe me when I tell you that I tried—I absolutely cannot remember/find an exact date for this; too, the timeline is kind of squirrelly: I definitely remember both my parents together there with me, which puts this taking pace at least some time before the summer of 1995 (when they were divorced), but I also have a hazy recollection of someone giving up their aisle seat to my mother, her being heavily pregnant at the time with my little brother, who was born in January of 1993. Not to mention, before the event, the church where this was all taking place showed a video package that had footage of promo work Jake had done during the buildup to that awful Spin the Wheel, Make the Deal/Coal Miner’s Glove match at WCW’s Halloween Havoc 1992, which then puts the event taking place sometime at the tail-end of Roberts’ WCW run. Maybe.

Nevertheless, exactly when I watched Jake preach in Fitzgerald, Georgia isn’t really what’s interesting or important here. What is interesting, however, is this: I started thinking the other day about seeing Jake that night. Now, I’ve been a wrestling fan since about 1989, and, as aforementioned, Jake was one of my absolute favorite wrestlers as a kid and easily makes my top twenty list today (his promo work and mic skills alone could crack such a list, but Jake at his best [i.e., cleanest and most clear-headed] was also a very good professional wrestler). I was absolutely captivated by Jake, and though it wouldn’t be until later on in my teenage years that I would fall out of favor with organized religion entirely, I still didn’t go watch him preach that night because I thought he would move me religiously; more so, though I didn’t realize it at the time (you know, I was a kid), I went to watch Roberts preach that night because I thought he would move me as a wrestler who is also a human being. I went in the purest state one can go to such a thing: a kid wanting, at the very least, just to be in the same room with one of his heroes.

But anyway, I digress: So, I found myself thinking back on all of this—fondly, for the most part, but occasionally a bit of a dark cloud will hang over my memory of Jake here (this period of time in his life could be looked at as a brief calm before a disastrous storm full of depression, pills, and whatever illicit substance Jake could get his hands on). Mainly, though, these thoughts are mostly filled with questions about a greater picture w/r/t wrestling and religion as a whole: That is, why the fuck do these two seem constantly to be forced to interact or interconnect with one another? It seems rather too easy or too cynical to say that someone like Jake—or any other religious wrestler—taking so intensely to religion that he tours parts of the country (for a fee, mind you) to speak about his religious conversion (as well as to sell cassette tapes [this was the ‘90s after all] of previous sermons and autographs after the show) equates to a lack of sincerity w/r/t his—or others’—finding religion, using such a thing as nothing more than a means to get to a very profitable end and shill to an already established fan base (no doubt, though, this certainly exists to some extent, whether or not the wrestlers are one hundred percent conscious of it).

Is it possible for wrestling and religion to mix without coming across as completely insincere or utterly offensive?

In this respect, then, is it even possible for wrestling and religion to mix in any way without coming across as either completely hack and insincere or utterly offensive? So, what I intend to do here is to try and unpack wrestling’s long and complicated relationship with religion—from religiously themed gimmicks and angles to the use of religion to either draw heat or get a certain wrestlers over—in order to attempt to make some sort of sense out of the two’s constant and tenacious pairing and try to figure out if the two have anything at all in common that could warrant such a connection in the first place.

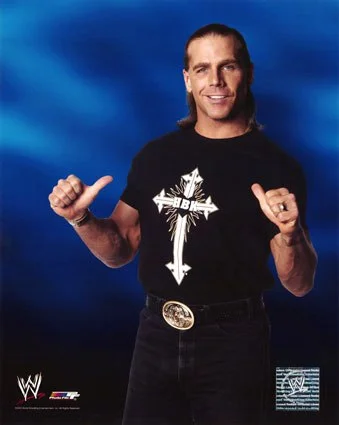

OK so, wrestling’s religiously themed angles and gimmicks have always been . . . well, weird. Take, for instance, the very infamous Vince and Shane McMahon vs. Shawn Michaels and “God” match at that year’s Backlash pay-per-view. Just that sentence alone is already pretty wacky, but, for clarity’s sake, here’s a bit of background about the angle as a whole: Like Jake The Snake, Shawn Michaels had his fair share of demons to contend with (as the wrestling world likes to say). I’m not writing anything here that hasn’t already been well documented—mostly by Michaels himself—in the past, particularly in his 2014 autobiography Wrestling for my Life: The Legend, the Reality, and the Faith of a WWE Superstar. “Worse, my life was a wreck,” Michaels writes.

“I liked being loved. And I liked being hated. I might even have liked being hated more. But outside of that ring, my life had spiraled so out of control—drinking too much […] doing drugs, popping pills—that I did not like who I really was. A winner in the business, I had become a loser in life.[1]”

Michaels, however, would clean up and become a shoot born-again Christian in the midst of his first retirement from wrestling in 1998. Again, Michaels writes: “I became a Christian in April 2002, a little more than four years after injuries forced me to retire following the Steve Austin match [at Wrestlemania XIV].”[2]

Also in 2002, Michaels would officially come out of in-ring retirement. Now, during this time, Shawn’s newfound Christianity wasn’t necessarily a secret: “I also started incorporating Christian words and symbols into my wardrobe,” he writes. “I wore overt Christian T-shirts into the ring, such as shirts that included Jesus’ name or made a declaration such as ‘He Is Risen.’”[3]

Never one to eschew an opportunity for a storyline, and following their match at Wrestlemania 22 wherein Michaels would best McMahon, Vince declared shenanigans and claimed that Shawn’s newfound Christianity meant that the match had been an unfair one—Shawn only won because God was on his side, so to speak. So, in the wacky world Vince McMahon lives in, the WWE CEO booked a match between himself and his son Shane vs. Shawn Michaels and “God” that would take place at that year’s Backlash pay-per-view. Mainly, though, this had more to do with setting up Vince’s character as some cartoonishly egotistical and delusional heel than with Michaels’ born again Christianity.

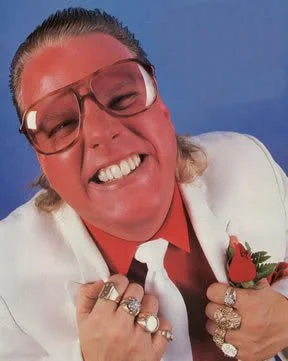

However, as far as religiously themed gimmicks go, mainstream wrestling has tossed countless examples our way. A lot of these gimmicks, mind you, were extremely short-lived (and for good reason): You can put wrestlers like Friar Ferguson (who would go on have the—possibly worse—Bastian Booger gimmick) and Mordecai (sort of the anti-Undertaker) on this list. There were also some more ambiguous religious gimmicks that stuck around for quite a while. Brother Love is perhaps the best example here and, though never overtly saying the word “God” (he would instead preach the word of Love), this gimmick would begin to scratch the surface of an interesting thing that mainstream wrestling (particularly the WWE) does when it comes to religion, especially Evangelical Christianity. That is, Brother Love was, first and foremost, a heel, a cartoonish parody of snake oil preachers like Jimmy Swaggart, Robert Tilton, Peter Popoff, et al. Now, though Brother Love undoubtedly fell flat in the long run, this ironic take on Evangelical Christianity that the WWE seemed to be trying to do is fascinating in retrospect because it illustrates pretty clearly a bifurcation w/r/t religious (specifically in this case Evangelical Christian) gimmicks to which WWE’s audience at the time would react to in two distinctly different ways.

People were beginning to become bored of the prayers/vitamins angles and cartoonish gimmicks

For the first, let’s go back for a bit to Jake “The Snake” Roberts and his return to the WWE at the 1996 Royal Rumble pay-per-view. During this whole second run in the company, Roberts was booked to be this newly born again Evangelical Christian (with new [Christian themed?] Albino Burmese Python, named rather uninspiringly “Revelations,” in tow). This was, of course, in kayfabe, but as I mentioned earlier, Roberts at this point had really become a shoot born again Christian. Now, for a very short while, Jake’s new religious conversion gimmick was pretty over. This was particularly helped by Roberts’ part in ushering in perhaps one of the most iconic phrases in WWE history: Austin 3:16. Too, his feud with pro wrestling’s own living, breathing flotsam, Jerry “The King” Lawler, seems to have been fairly well received despite its cringe-worthy nature at times. (A particular point to note w/r/t the uneasiness of the Roberts/Lawler feud: According to Jake’s Pick Your Poison DVD, Lawler once spit actual, no bullshit whiskey into Roberts’ face, who was in the middle of recovery at the time.)

Nevertheless, what’s interesting here is the comparison of how Roberts was booked vs. how he was received by the audience. Now, there’s still a pretty intense debate going on w/r/t exactly when WWE’s famed Attitude Era officially starts, and I certainly don’t want to weigh in on that debate here, but it’s very safe to say that it’s around 1994 or 1995 when you can definitely begin to feel a change in the WWE audience. That is, people were beginning to become bored of the prayers/vitamins angles and cartoonish gimmicks the WWE had been pushing for a little over a decade, and were clamoring for something fresh and new. So, after the shock of Jake’s return to the WWE wore off, audiences really just sort of shrugged their shoulders w/r/t Roberts in general. He would go out, cut a promo about how Jesus saved his life, state a million times that he’s now here as an example for kids to understand that they need to stay away from drugs and alcohol, and in most cases the crowd would just stare and politely golf-clap simply due to the fact that they knew they were supposed to clap for Jake because he was a ‘face. It was far less of a sincere pop and more so an “OK, we’re clapping for the ‘face, let’s please move on” type deal. It’s the most apathetic heat I think there’s been in the post-Hulkamania era of mainstream wrestling. Take Jake’s born again Evangelical Christian gimmick and pull it back about five or ten years and he would’ve been over as hell, but the attitude (forgive the pun) of the crowd in the mid- to late-‘90s was so far removed from the prayers/vitamins of the ‘80s and the overblown cartoons of the early ‘90s, that this sort of religious redemption gimmick was dead almost as soon as it took off. The crowd just weren’t having it. Which brings us to Dustin Runnels/Golddust and an altogether different type of reaction to the religious conversion gimmick.

So, during the aforementioned Attitude Era, Dustin Runnels’ Goldust gimmick was drawing a lot of heat. Now, there’s some question as to whether this was a good thing (i.e., playing on the sometimes very blatant and nasty homophobia of an Attitude Era crowd and forcing them to confront such a thing) or a bad thing (i.e., othering the homosexual community even more by creating a gimmick that lampooned their culture and portrayed the only sexually ambiguous character in the WWE as a heel). I’ll leave this debate for another time. However, at one point in Runnels’ run as Golddust he got sick of the character and became a kayfabe born again Evangelical Christian. Appearing under his real name, Runnels would start to label himself the spokesman for the Evangelists Against Television, Movies, and Entertainment group. (Yes, that spells out EAT ME; someone in the writers’ room was hard-up for a joke). Runnels would then run vignettes demonizing the Attitude Era’s far more loose morality, urging viewers to turn off their TVs in order to stop sinning.

Runnels gimmick here is meant to ironically call attention to an increasingly vocal Religious Right in the United States that had been condemning the WWE for its programming for quite a while. However, the audience’s reaction to Runnels’ Evangelical Christian gimmick was exactly the opposite of their reaction to Jake’s. Gone was the apathy and polite golf-clap pops, replaced instead with utter hate and vitriol. This was the religious gimmick the Attitude Era crowd seemed to be searching for: someone to hate for his/her blatant holier than thou viewpoint. Sadly, though, the blowoff to this whole gimmick would be a play on the eschatological phrase “He’s coming back.” Clearly, the implication is that Runnels is playing off the popularity of certain apocalyptic scenarios famously pushed in the Left Behind series of books and movies, but, in the end, the “He” referred to here was Golddust himself, so the whole leaving Golddust behind angle just became useless, inbent fodder to hype Goldust’s return, and the crowd seemed altogether pretty uninterested about the whole thing in the end.

The Sheik was booked to be the epitome of the Othered Muslim: cheap, xenophobic heat

Moving away from Evangelical Christianity, mainstream wrestling’s treatment of Islam has been pretty wretched for quite a while. This has mostly to do with the weird, and oftentimes shitty, politics games wrestling likes to play from time to time. Take, for example, The Sheik in the ‘60s, who would come to the ring and perform salat at the beginning of each match to the not so subtle disdain of the audience. In other words, The Sheik was booked to be the epitome of the Othered Muslim: it was cheap, xenophobic heat designed to illicit a reaction from the crowd not because of what the heel does or stands for, but simply because the person in the ring didn’t look or think like the members of the audience. Unfortunately, the Othered Muslim angle has been one of wrestling’s most consistent. Notable examples of this are plentiful, but there is, however, one Othered Muslim gimmick that seems to take the cake, so to speak, when it comes to wrestling’s insensitive religious booking: WWE’s Muhammad Hassan.

Lawler and JR sound like every Facebook post that either begins or ends with #AllLivesMatter

Now, at first, Muhammad Hassan was a very interesting gimmick: A post-9/11 Muslim character that was using the United States’ extreme and utterly ridiculous xenophobic sensibility at the time to draw heat. Of course, this gimmick so far has just been another re-hashing of the Othered Muslim, but where Hassan was different was in the fact that he absolutely had a legitimate gripe. Hassan’s gimmick wasn’t that he was a cartoon parody of a Muslim, but that he was legitimately upset about the way Muslims in the United States were being treated following the attacks of September 11th. This is all, again, cheap heat, but it’s at least interesting cheap heat that can work to create discourse. (The forever-wonderful Brian Zane over at Wrestling With Wregret explained in his very first video how this gimmick could’ve gone over well better than I ever could, so I would suggest checking that out as soon as possible.) However, things began to turn for the Hassan gimmick, and I think you can see such a turn coming in a pretty ridiculous in-ring debate that aired live on RAW between Hassan, Jerry “The King” Lawler, and good ole Jim Ross. It’s worth noting that, in this debate, both Lawler and JR sound like every Facebook post that either begins or ends with #AllLivesMatter—attempting to foil Hassan’s claim of racism with blanket, meaningless statements like “There are racists in every country” or “In America, you either love it or you leave it.” What’s definitely a harbinger for the disaster that would become of the Muhammad Hassan gimmick is the crowd’s pop to Lawler and JR’s ridiculous booking here.

Hassan comes out, kneels as if in prayer, and summons a number of masked “terrorists” who proceeded to attack the Undertaker.

Cut to 2005 and the culmination of tastelessness w/r/t this gimmick: Hassan had been feuding with the Undertaker for a while, and the two were scheduled to have a blowoff match at that year’s Great American Bash (note that it’s not a coincidence that this match was scheduled for this particular pay-per-view: more cheap heat opportunity, I think). But, before the pay-per-view, the Undertaker was having a match on television and, just after he gets the pin and his music began to play, Hassan comes out, kneels as if in prayer, and summons a number of masked “terrorists” who proceeded to attack the Undertaker. As if things couldn’t get any worse, Hassan then prays to Allah and locks in a camel clutch on the Undertaker for good measure. Holy shit. Now, this alone is taking the Othered Muslim gimmick to such an extreme that it becomes far too real far too quickly. Instead of throwing the United States’ xenophobia at the time back in its face, Hassan’s attack on the Undertaker did everything to reinforce this xenophobia. It no longer became an open discourse, it just became the pinnacle of Islamaphobia from earlier periods of wrestling—the paragon of the “scary” Muslim. As if this couldn’t get any worse, Hassan’s “terrorist attack” on the Undertaker took place the very same day as the 7/7 London bombings, and the WWE still aired the episode.

OK, so far I’ve probably come across as a bit negative w/r/t mainstream wrestling’s treatment of religion, such a thing reading as either hack, insincere, or absolutely offensive. And, to be honest, most of it is just that. This being the case, then, is there really anything sincere and/or positive to gather from wrestling and religion at all? Well, the short answer is yes, but maybe not in the way that seems obvious at first glance. That is to say, to me, wrestling and religion both fall under the same overarching category: the ability to create meaning. I say this with the biggest of hearts—I’m absolutely not trying to disparage anyone’s religion by snidely comparing such a thing to a pro-wrestling show, only that both deal so purely with the creation of meaning, of communication, that the similarities are hard to ignore. Hear me out.

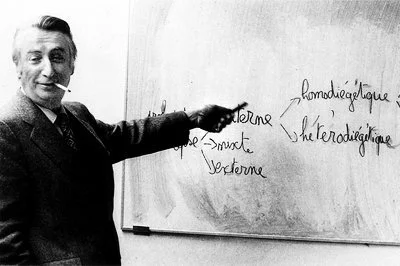

In his now famous essay “In the Ring,” the brilliant French structuralist turned post-structuralist, Roland Barthes, writes the following about wrestling (this essay was previously titled “World of Wrestling” and I have no idea why they changed it, but in my copy of Barthes’ essay collection, Mythologies [where the essay appears], it’s titled “In the Ring”; too, keep in mind that Barthes was particularly talking about French pro-wrestling in the late 1950s, so a lot has changed w/r/t the business nowadays, but still, the overall theme of the essay remains wholly intact):

“Wrestling is a sort of diacritical writing: above the fundamental signification of his [or her] body, the wrestler arrays episodic but always welcome explanations, constantly aiding the reading of the combat by certain gestures, certain attitudes, certain mimicries which afford the intention its utmost meaning. […] Each moment of the wrestling match is therefore a kind of algebra which instantaneously discloses the relation of the cause with its figured effect.[4]”

Now, Barthes’ admittedly purple as all fuck writing aside (he definitely liked to show off, but that doesn’t make him any less brilliant), what he’s getting at here is so incredibly important. That is, what Barthes’ is beginning to realize here w/r/t wrestling is that such a thing absolutely rejects any sort of known logic of signs, opting instead to create and recreate over and over again a wealth of signifiers in order to create meaning, if only for as long as the two wrestlers happen to be in the ring. We as audience members forget for a moment that, say, Bayley’s shoot name is Pamela or that Finn Bálor isn’t really sometimes human and sometimes demon or that the Undertaker isn’t really a goddamn undead wizard/zombie/magician/cult leader or whatever.

That is, for the time that these wrestlers are in the ring, signs are replaced by infinite signifiers that do one thing equal to any and all storytelling: they create meaning through mythology. But wrestling doesn’t pull this concept out of thin air; no, wrestling shares this concept—to a degree—with religion. Barthes continues:

“When the hero [‘face] or the bastard [heel] of the drama, the [person] who has been seen a few minutes earlier possessed by a moral fury, enlarged to the size of a kind of metaphysical sign—when this figure leaves the wrestling hall, impassive, anonymous, carrying a gym bag and [their wife or husband] on [their] arm, who could doubt that wrestling possesses that power of transmutation proper to Spectacle and to Worship?[5]”

But wrestling’s take on meaning and religion’s take on meaning do differ in various ways. Yes, both are myth-making perhaps at its finest, but the most obvious difference has to be that wresting is absolutely self-aware of it’s myth-making, while religion isn’t. In fact, it can’t be—such self-awareness lowers the stakes, and it doesn’t take a genius to point out that the stakes are much higher in religious myth-making than in wrestling’s. However, I think the best way to describe this is not to say that wrestling and religion are one in the same, because they’re obviously not, but more so that wrestling is religious myth-making done through a hefty serving of what another French post-structuralist, Jacques Derrida, refers to as “play.”

In his essay “Structure, Sign and Play in the Discourse of the Human Sciences,” Derrida writes the following:

“Play is the disruption of presence. The presence of an element is always a signifying and substitute reference inscribed in a system of differences and the movement of a chain. Play is always play of absence and presence, but if it is to be though radically, play must be conceived of before the alternative of presence and absence. Being must be conceived as presence or absence on the basis of the possibility of play and not the other way around.[6]”

Here, Derrida is talking strictly about creating meaning and how, to him, the only way to even begin to approach such a thing is through play. That is, meaning can never be achieved by simply signifying a referent; instead, it can only be part of a dissemination of meaning that signifies an infinity of signifiers. Play, therefore, is the exploration of meaning, allowing for an infinity of meaning to exist. And, honestly, that’s exactly what wrestling is to me, what makes such a thing, if you’ll forgive my cheesyness, so beautiful. The story never stops, characters and gimmicks grow and change, and meaning is only “meaning” during the match: it’s forever subject to change. Pro-Wrestling, therefore, uses religion’s power of myth-making, and turns such a thing into a self-aware play of language and meaning that’s so utterly powerful it has been telling stories for decades. This, then, is what I’ve come to realize that religion and wrestling have so beautifully in common: the ability to simply create meaning through mythology.

[1] Shawn Michaels, Wrestling for my Life: The Legend, the Reality, and the Faith of a WWE Superstar (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan, 2014), 18.

[2] Ibid., 47.

[3] Ibid., 57.

[4] Roland Barthes, “In the Ring,” Mythologies, trans. Richard Howard and Annette Lavers (New York: Hill and Wang, 2013), 6 – 7.

[5] Ibid., 14.

[6] Jacques Derrida, “Structure, Sign and Play in the Discourse of the Human Sciences,” Writing and Difference. trans. Alan Bass (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1978), 292.